The phone rings shortly before midnight on a secure line. It is the source who just drove me back to my hotel.

Someone followed us, he says. They just took photos of the entrance to my building. Now they are in their car, waiting.

I am the only Danish journalist left in Russia.

Matilde Kimer from the broadcaster DR was stopped at the airport and expelled. But I got in with no questions asked.

Only once I head deep into the country do troubles start to happen.

I have travelled back to Russia to cover this weekend’s local and regional elections. For years all elections have been strictly controlled by the regime. But at the most recent elections, this is also where cracks of Russian dissent appeared from below.

But this time everything is just different.

So this is not the story of an election. Nor is it a story about me. It is the story of a country where dissent is suppressed like never before.

By the powers that be, by the security services and by an all-consuming, angry patriotism.

Russia’s centre of »vile liberalism«

Since Russia invaded Ukraine six months ago, the biggest question in the West has been why more Russians are not speaking out against the war.

That is why I have headed for Yekaterinburg.

This is a city of millions, located at the foot of the Urals mountains that lie between the European and Siberian parts of Russia, and often referred to as the country’s third most important city after Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

Barely three years ago, Berlingske wrote about Yekaterinburg as the most striking example of a new type of activism in Russia. The city has an independent spirit, political consultant Yaroslav Shirshikov told us then.

More recently, Yekaterinburg was given another predicate by Russia’s perhaps most influential propagandist, television host Vladimir Solovyov: »A centre of vile liberalism,« he called it.

If anyone dares to challenge President Putin’s agenda, I think, surely it must be here.

But the first part of the answer hits me as soon as I step off the plane.

“Spy!”

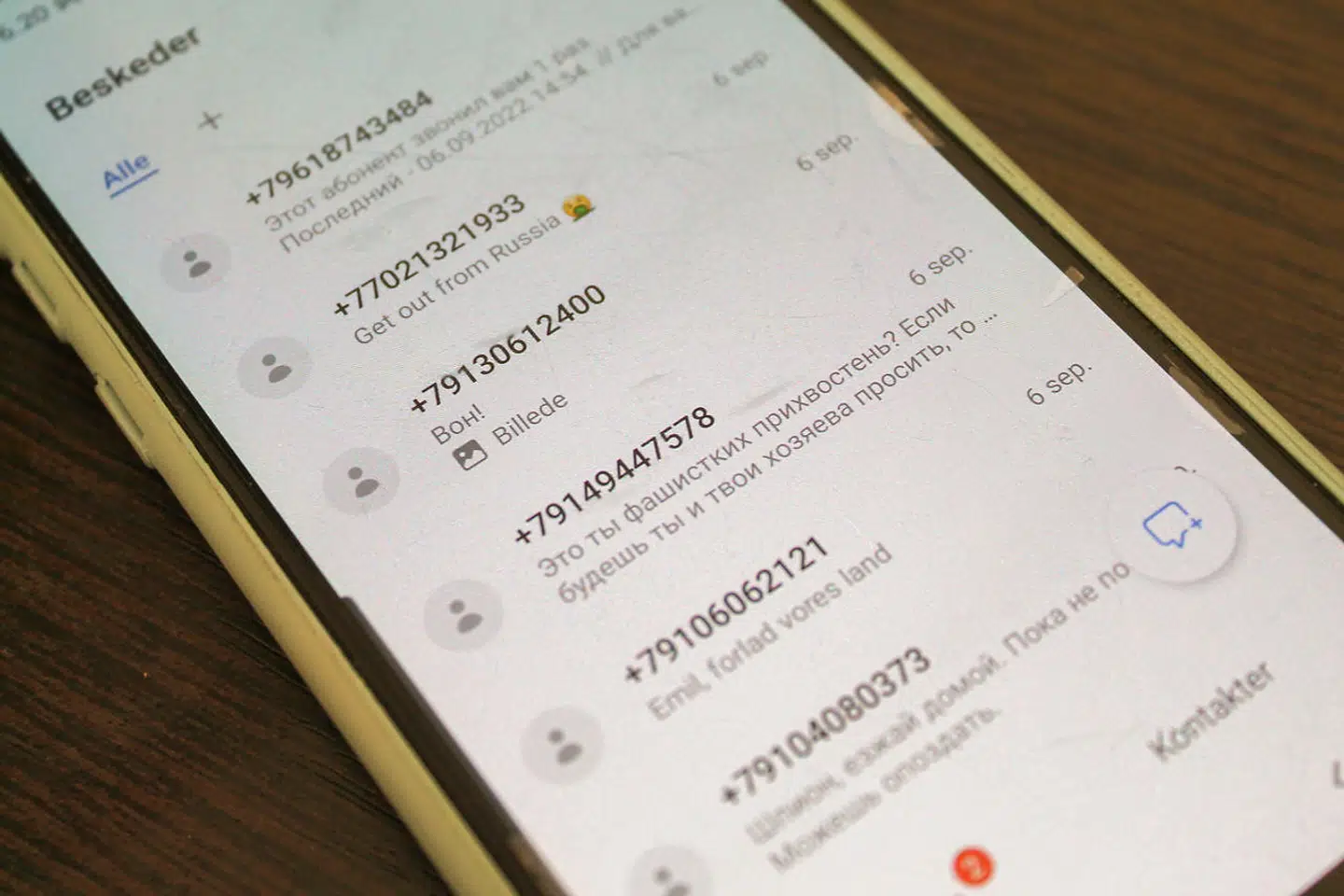

When I switch my phone back on, I get a barrage of messages and calls:

»Spy! Get out of this town while you still can!« reads one of the hundreds of threats pouring in.

This is all because Yaroslav Shirshikov posted on Russia’s answer to Facebook, VKontakte, that he is due to meet another reporter from the Danish newspaper Berlingske. And now the local patriotic media outlet Ural Live has dug up everything else, including the fact that I once trained as a language officer with the Danish Defence.

Somehow, they also found my Russian and Danish phone numbers and published them along with a photo of me, urging people to phone »the spy«.

Far worse, Vladimir Solovyov, the well-known television host, has promptly shared the post with his 1.2 million followers on Telegram.

And now a fair share of them are besieging me with calls and threats on every type of messaging service they can think of.

»These are our idiots,« says Yaroslav Shirshikov, at first dismissing them as harmless provocateurs.

But when I arrive at Shirshikov’s small office, several local reporters have also turned up to our interview. One of them sets up his camera to point only at me.

He asks if I am an expert on military equipment and whether that is why I have come to town.

I reply that I am here to cover the election, and try to focus on interviewing Shirshikov.

Seven years for a joke

After the successful protests in 2019, Yekaterinburg’s grassroots movements actually had a lot of momentum, Yaroslav Shirshikov tells me.

The city council set up a committee for “concerned citizens” to seek their advice.

It was even possible to get the 15,000 signatures needed to raise a proposal to bring back direct elections for the mayor’s office.

But the proposal was voted down on its first reading, and now the citizens’ committee is only consulted on where to build a church or who to name a street after.

As for Yaroslav Shirshikov, he was sentenced to 18 months in prison for inciting mass riots and jokingly referring to a Russian top official as a Polish spy.

»I ended up serving seven months behind bars. For a joke,« Yaroslav Shirshikov says.

»It seems more people in Yekaterinburg were ready to protest against a building in a public square than on real political issues,« says Vladislav Postnikov who has also joined the interview.

Last year, he ran as an independent candidate for the State Duma but lost to the candidate from the governing party, United Russia.

»Under the present circumstances, there’s no space in Russian politics for someone with my views, so now I’m just a journalist,« Vladislav Postnikov says.

This year no genuine opposition candidates were allowed to run in the election, Yaroslow Shirshikov tells me. Not even the Communists or the Party of Pensioners dare to talk about prices going up and up.

»This is not an election. It’s fiction.«

»So how do people feel about the special operation,« I ask, using the only phrase legally allowed in Russia to describe the war in Ukraine, knowing I am being filmed for Russian television.

»I was just fined 40,000 roubles for making a statement about the special operation, so I have no comment,« Yaroslav Shirshikov replies.

»I was fined 100,000 roubles for writing about it,« Vladislav Postnikov says.

»And I was fined for protesting,« says a third person, out of the very few people in the room.

People are afraid to speak their minds in public, Vladislav Postnikov explains. That is why opinion polls indicating some 76 percent popular support for the war are simply not reliable, he thinks.

»But you probably see how we feel about the special operation,« Yaroslav Shirshikov says, bursting into laughter.

Threats to power

My phone still keeps ringing non-stop, as it has been for four hours now, as I leave Shirshikov’s office.

On foot we head through the darkness along Lenin Avenue towards the next appointment of the evening, while Vladislav Postnikov points to the city’s landmarks and tells me about them.

Yekaterinburg always had a history of being a breed apart.

In tsarist Russia it was a centre of revolutionary movements.

After the Second World War, this is where Stalin sent Field Marshall Zhukov, fearing he would pose a threat to power in Moscow.

This was where Boris Yeltsin was born and started his career.

More recently, the city’s former mayor for several years, Yevgeny Roizman, was the last prominent politician in Russia to openly criticize the war.

Last month, Roizman was arrested for discrediting the army. Somewhat surprisingly, he was quickly released again but banned from using the internet and communicating with anyone other than his family while his trial proceeds.

»I think they were afraid to stir up the protest voters that Yekaterinburg still has plenty of,« Vladislav Postnikov says. »But I’m afraid they’ll give him a harsh sentence after the election.«

»We don’t know what’s going to happen to any of us after the election,« Yaroslav Shirshikov adds.

Afraid of the truth

We have arrived at the local section of the human rights organisation Memorial.

Outside, the street is empty and quiet. I step down into a basement and walk along narrow corridors strewn with papers, flyers and posters until I suddenly find myself in a long room with 17 volunteers crammed into it.

»They’re already writing about you!« one of them says as I enter.

»Yes, they say I’m a spy,« I reply and show them the messages that are still pouring in.

»A badge of honour!« the volunteers respond, laughing.

Not a single person in this room has not been fined or detained over the past six months because of the war. Except for 17-year-old Igor. He just had a friendly visit from the police at home.

They used to take to the streets once a month to protest with flags, posters and music on behalf of political prisoners in Russia. Since the war broke out, they have been denied permission for any kind of demonstration, even for peace.

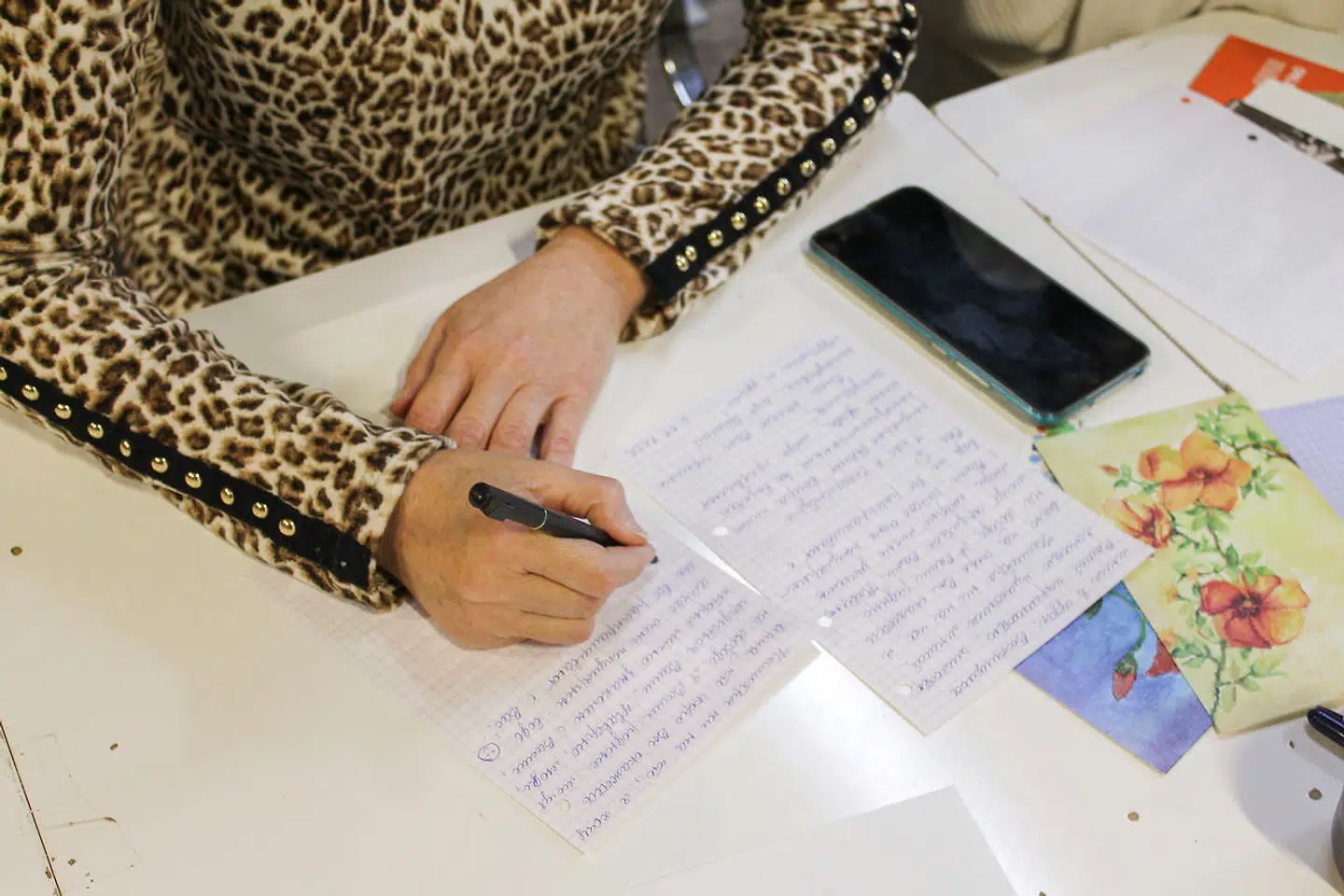

Now they meet here instead and write letters to political prisoners.

»Last month they wrote to me too,« Yelena Shukayeva says with a grin. She is a journalist and used to work at Novaya Gazeta, a leading independent newspaper that has now been shut down.

So far, she has been given five fines of 40,000 roubles each and 14 days in prison, the latter for something she posted on Facebook five years ago.

Another volunteer, Katya, has accumulated half a million roubles in fines for participating in war protests.

They have already raised money for the fines through online crowdfunding, but none of them intend to pay.

»Then the state will only spend it on more rockets,« Yelena Shukayeva says.

Memorial’s head organisation in Moscow was shut down by force. But in Yekaterinburg it functions as an independent organisation that would require an independent process to shut down. The police have already been here looking for ”extremist material”.

The letters to the prisoners are one of the few remaining legal ways of showing dissent.

But there are some in the city who use illegal methods, they say. Some paint blue and yellow graffiti, some put up stickers, some write slogans on money notes.

Others help Ukrainian refugees. There is even someone playing Ukrainian songs.

»I call the war a war and discuss it with people,« says Katya who has clocked up 1.5 million roubles in fines.

»I tell them I know what they are being told on TV. I actually watch it. I wake up in the middle of the night and watch Vladimir Solovyov. But when I then ask people to watch the other things that I’m also watching, they get scared.«

»They say it’s because I want to show them propaganda. But really, they’re afraid I’m right,« Katya says.

What tomorrow brings

When we leave the basement, I notice two guys parked in the road in a darkened Skoda.

They switch on the lights and follow us without making much of an effort to hide it.

Some of the volunteers from Memorial insist on driving me back to my hotel. They try to take a detour, making random turns.

But when we reach the hotel, the Skoda is already there.

When I get to my room, the head of Memorial, Anatoly Svechnikov, calls me on a secure line.

A young guy in a dark grey hoodie just took some photos of where I live. Now he is in the Skoda with another guy, waiting.

Anatoly Svechnikov can’t say if I am in any danger.

It is one thing if they are »just« the same patriots who are behind the threatening phone calls and messages. We don’t know what they are capable of, but it is easy to hide from them.

If it is the FSB security services, that is a completely different thing.

»And the boundaries of what can happen in Russia today are constantly shifting,« Anatoly Svechnikov says.

Ten minutes later, I leave the hotel by a rear exit and check into another hotel. Apparently without being followed.

The next day I fly out of the city.

Shortly after, Ural Live reports to its readers that, thanks to them, the foreign spy was scared off.

Vladimir Solovyov promptly shares the news with his 1.2 million followers.

The journalist Vladislav Postnikov writes to ask if I arrived safely.

»It’s hard to say what will happen in a few years. Or just in six months. Since February, a lot of things have really been turbo-charged,« was one of the last things he told me before saying goodbye.

The next morning, his flat is raided by the police and he is brought in for questioning under charges of being connected to a Russian resistance movement in Ukraine.

The following day, the journalist Yelena Shukayeva from Memorial is put on the Russian Ministry of Justice’s list of »foreign agents«.

Emil Rottbøll is Berlingske’s Russia correspondent

Translated by Bibi Christensen